Closed-loop cooling in Oracle AI data centers

What it is, how it works, and why it matters for local water supplies

By Travis Grizzel, Architect, Oracle Cloud Infrastructure—Feb 9, 2026Read this announcement in Spanish

When a new data center comes to a community, one of the first questions that comes up is: “Are you going to use our water?”

That question is understandable, and appropriate. Water matters. It sustains families, businesses, farms, and the ecosystem. And in many places, it’s already under pressure. Community members are right to want a clear explanation of what changes, and what doesn’t, when a data center arrives.

Oracle is committed to helping communities understand the impact of its new AI data centers, starting with details on how our cooling works and what that means for local water. In short, at our AI infrastructure data centers—including upcoming ones in New Mexico, Michigan, Texas, and Wisconsin—we plan to deploy a variety of cooling methods like closed-loop cooling that do not rely on continuous consumption of potable water. These are deliberate engineering decisions designed with local communities in mind.

No one size fits all

The computing equipment inside data centers does useful work, and as a byproduct, it produces heat. Cooling systems enable us to move heat away from the equipment so that it can operate reliably.

There are a few common ways data centers do this today. To understand how those techniques differ, it helps to consider everyday household equivalents.

Some cooling approaches are basically the “fan in the window.” They move air through a space and push warm air out. This approach works well in colder climates. Another approach is to use evaporative cooling, more like a swamp cooler or the way sweat cools your skin. The tradeoff here is that the water is consumed and must be continuously replaced.

A third approach is what many of us have in our homes, particularly in warmer climates; air conditioning. An air conditioner is a closed-loop system, because the cooling fluid inside it circulates in a sealed loop and is reused. Data centers can use the same basic idea at larger scale.

In practice, responsible data center design means choosing a cooling approach that keeps systems running reliably, while considering the impact to the local environment, even if resources are available in abundance. Climate matters. Local resources matter. And for communities concerned about water, the most important distinction is simple: Does the cooling system rely on evaporating water day after day, or does it recirculate a cooling fluid in a closed loop?

A closer look at closed-loop, non-evaporative systems

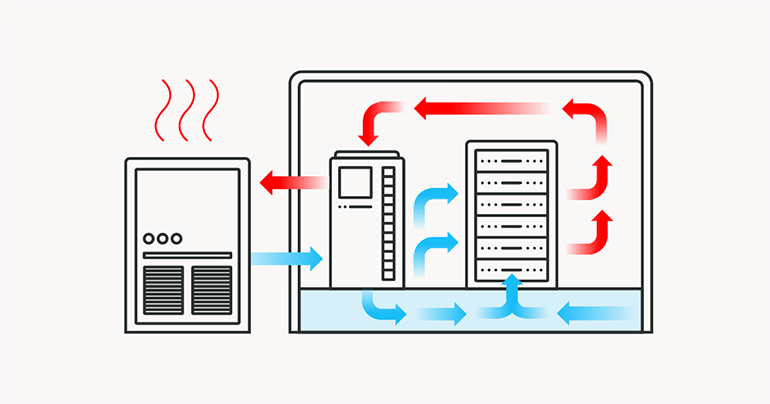

In a closed-loop system, like your home air conditioner, the cooling fluid stays within sealed pipes and is repeatedly reused, rather than consumed.

Similarly, a closed-loop, non-evaporative cooling system in a data center works by recirculating air using cooling coils and fans, delivering conditioned air back to the servers. The cooler air allows the servers in the data center to operate reliably and efficiently. And in practical terms, these data center grade air conditioners are designed to not draw down a community’s water resources the way that an evaporative system would.

Introducing direct-to-chip, closed-loop, non-evaporative cooling systems

In the AI data centers Oracle is building today—including those in New Mexico, Michigan, Wisconsin, and Texas—we use an evolution of closed-loop designs: direct-to-chip, closed-loop, non-evaporative, cooling systems. Instead of relying on cooling the room air, we remove heat closer to where it’s created, at the servers themselves. This proven variation of a closed-loop system is the next step in modern data center design, allowing us to be as efficient and reliable as possible.

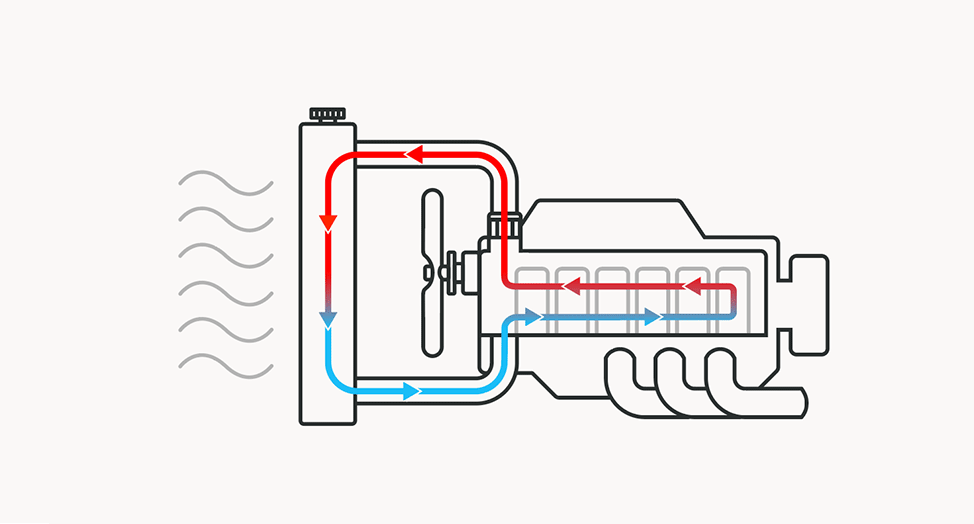

The simplest way to picture a direct-to-chip closed-loop is the cooling system in a car.

In your car, coolant circulates and absorbs heat from the engine, then it releases that heat through a radiator, where air cools it back down. The liquid doesn’t disappear. You don’t refill the system every day. The coolant keeps circulating in a loop, doing its job over and over. The key is that the cooling happens directly at the source of the heat.

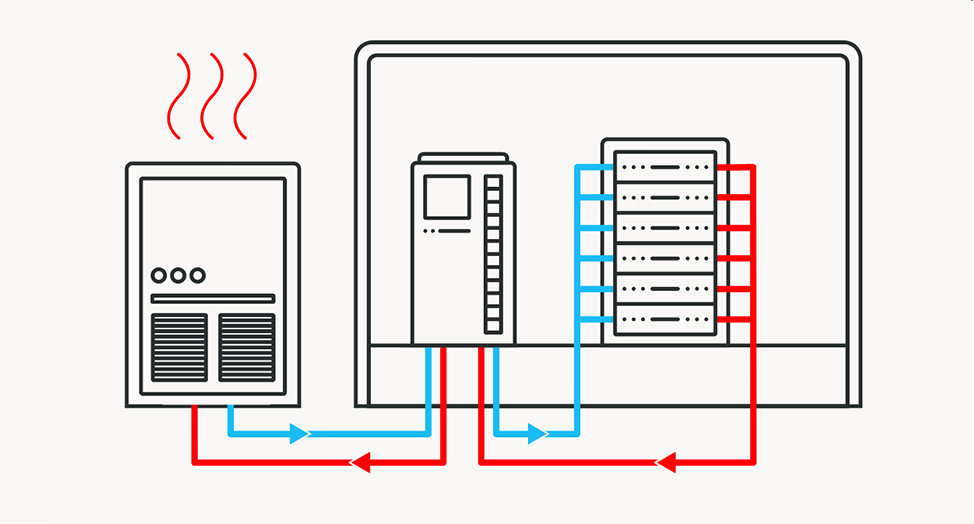

The same type of loop is used in the newest Oracle AI data centers, just on a larger scale.

Inside the facility, equipment generates heat as it performs work, not unlike a car engine does. Like a car, there’s a one-time fill of liquid to the cooling system. Once heat is being produced, cool liquid circulates through sealed piping and absorbs the heat at the source: the servers, and more specifically at the processors themselves. The warmed liquid then flows to heat exchangers and radiator-like systems, where fans move outdoor air across coils to remove the heat. The liquid is cooled and recirculates to repeat the cycle. The cooling fluid remains in the system and isn’t used up.

In the simplest terms: The heat leaves the building; cooling liquid does not.

That’s the loop. To come back to the vehicle analogy, the water in the cooling loop is more like the radiator fluid in an engine than the gasoline. It’s part of the machine. It circulates. It’s not meant to be burned up. It’s reused. And that choice is deliberate.

Proven design, backed by data

It helps to put some scale behind the difference in cooling approaches.

Industry estimates vary widely based on climate and design, but the direction is consistent. One benchmark from the Uptime Institute estimates that a conventional, evaporative cooling system can use on the order of millions of gallons of water per year for each megawatt of IT load. As this evaporation happens, the water must be continually replaced.

In a direct-to-chip, closed-loop, non-evaporative design the cooling loop is initially filled using water delivered via tankers, and then it operates as a sealed, recirculating system. There is no evaporation, blowdown, or continuous makeup water requirement. That is, day-to-day cooling doesn’t depend on adding water. Top-offs are rare and occur only under abnormal conditions. Ongoing community water usage for cooling the data center is effectively zero.

At this point someone might reasonably wonder: Do you use any water at all?

Yes, but not as a consumable part of the cooling process. Once operational, daily water use primarily comes from typical office occupancy needs, such as kitchens, restrooms, and breakrooms, where usage is comparable to a typical office building.

Why all this matters for communities

For communities where data centers are built, these decisions aren’t an abstract engineering choice. Reducing cooling-related potable water use helps protect local resources and minimizes the likelihood that data center operations compete with other community needs.

Oracle is making deep investments in the communities where we build, not just in environmental stewardship but also in local hiring, partnerships with schools, and investments in local infrastructure. Approaches like direct-to-chip closed loop systems start from a simple principle: Water is valuable, and we should engineer accordingly.